Destination Place Des Arts

As the holiday season approaches, there are a number of reasons to come visit Place des Arts in downtown Montréal. For the first time in several years, Montréal has brought back the downtown Christmas market, a popular holiday season destination for families, seniors and children alike. During every visit I have made to “The Great Christmas Market” this year, I have noticed parents or grandparents with strollers walking through the artisan booths. With the abundance of department stores and seasonal light installations, the St. Catherine stretch is also a popular holiday shopping destination for all Montrealers. The underground city, to which Place-Des-Arts metro station is widely connected, is also an important point of interest in all seasons, especially in the winter. The Musée d’Art Contemporain, UQAM, and the Place-des-Arts theaters are also important to consider, as well as the multitude of summer festivals held there during the summer. Yet, Place-Des-Arts metro station has an inaccessibility problem which can present obstructions to many stakeholders who seek to reach this downtown entertainment destination.

Station Accessibility

We have covered in a past article some of the accessibility issues at Place des Arts, but we only briefly touched on the metro’s accessibility at that time. In this Station Spotlight, we continue our system-wide accessibility analysis with the aim to elaborate on the various barriers at the Place-Des-Arts metro station in order to complement our previous overview.

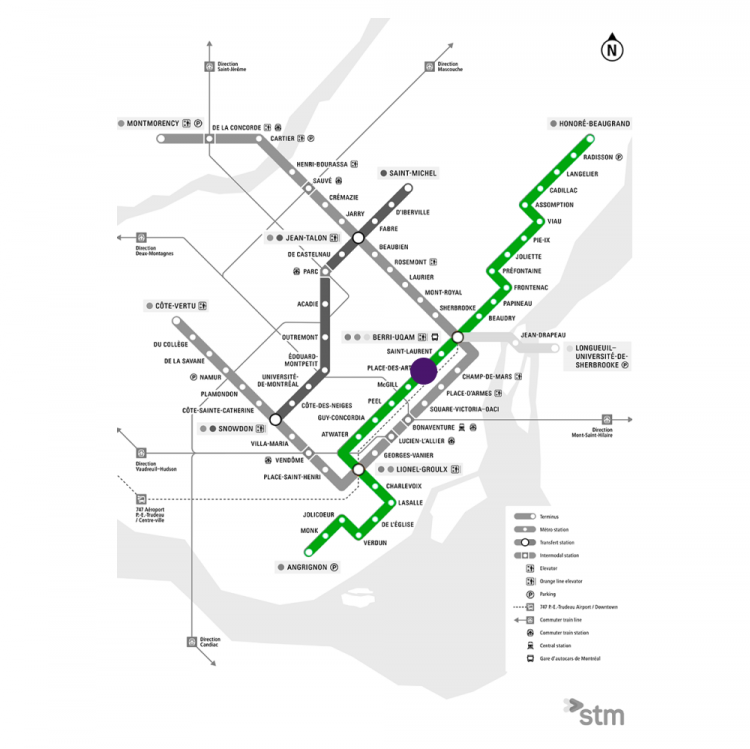

Place-Des Arts metro is located on the Green Line between Saint-Laurent and McGill stations. As we stated above, it is a very popular station essential to the social fabric and artistic life of the city. Spaces like these should be available for everyone to enjoy, so that all can contribute to the vibrant energy Place des Arts has the potential to provide. The metro station has 4 official entrances, though it can also be accessed through the Complexe Desjardins and the Place des Arts theater center via the underground city. Of the 4 entrances, none currently have an elevator. As can be seen on the station poster above, there are also no escalators going down, and there is only one exit which has escalators to go up. The northernmost De Bleury entrance (at the President Kennedy Avenue intersection) is currently undergoing construction to be integrated into a new building, and the STM is taking advantage of this construction to add an elevator and automatic butterfly doors to that entrance, which is planned to reopen in July 2022. While this represents progress for Place-Des-Arts station, it is nonetheless insufficient to make it universally accessible, especially given the De Bleury entrance is one of the furthest from the Place des Arts entertainment infrastructure, meaning it will likely require extra effort for passengers with reduced mobility to travel between their destination and the station entrance.

Barrier Awareness & Removal

A uniquely problematic feature of the Place-Des-Arts metro station is that one of the exits is physically inaccessible to some of the key stakeholders we mentioned above: full-height revolving-door style turnstiles prevent access for anyone with strollers or bikes. This accessibility barrier is clearly marked at the bottom of the stairs, but they are also located at the only exit that has an escalator from the platform. This means that if passengers pushing strollers, or carrying bikes or other heavy items tempted to exit using the escalators, they would have to turn back, walk down 21 stair-steps (there is no escalator going down), and walk to the other side of the platform where they can then take 21 stair-steps back up to an exit that will allow them to go through. Place-des-Arts is the only station in the system that has these turnstiles, so we must ask ourselves why they are there in the first place, especially given the current lack of adequate alternatives for strollers, bikes, and wheelchairs.

This is an example of an Orange-Cone Barrier, a removable obstacle which unnecessarily reduces accessibility. This is often the kind of obstruction that able-bodied users think little about but which causes great difficulties for key stakeholders with reduced mobility. Obstacles like these are unfortunately very common in cities. Think about the two trash days that every Montréal boroughs have, when bags and bins line the sidewalk. In interviews with some reduced mobility stakeholders, our founder Omer Juma heard many reports that those are simply days where it is virtually impossible to go out as the sidewalks become inaccessible. In the winter, these obstacles multiply: inadequate snow and ice removal can make sidewalks unpleasant at best, and perilous at worst. Have you ever found yourself at an intersection facing a large puddle of slush and icy water? Well, an able-bodied person can walk around the puddle, a mild inconvenience, but wheelchair users and parents with strollers rely on the curb cutouts —where the puddles are at their worst— in order to cross the street.

[Orange Cone Barriers are] often the kind of obstruction that able-bodied users think little about but which cause great difficulties for key stakeholders with reduced mobility.

These are not problems which require huge amounts of infrastructure or investment, they are simply not a priority for the city. In order to make our cities and our metro stations more accessible, we must be conscious of how tackling these little obstacles head-on can make a big difference.