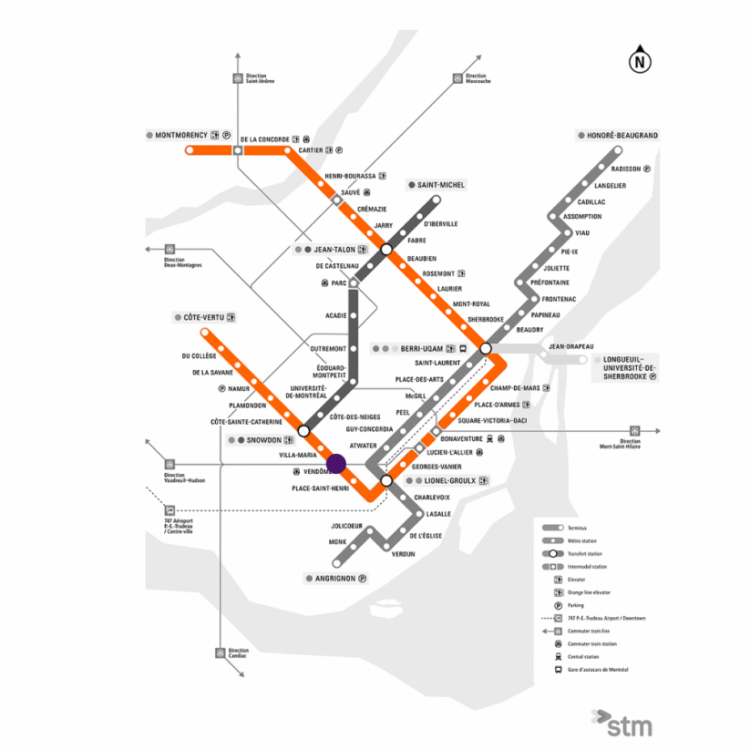

The Geographic Importance of Vendôme

Métro Vendôme is one of Montreal’s busiest stations. Not only is it a highly trafficked intermodal station with three Exo train connections, but it also is the nearest stop to the Glen Site of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). The new Glen Site is the largest of the four hospitals within the MUHC health centers: at its location by the Vendôme stop, it includes the Royal Victoria Hospital, the Montreal’s Children Hospital, and the Montreal Chest Institute.

Altogether, this means that universal accessibility is a crucial requirement at Vendôme metro station, especially considering that the passengers who are using the station to get to the hospital are even more likely to be part of the ten groups that we identified as most susceptible to accessibility obstacles in transit systems. Unfortunately, Vendôme’s metro station is a key case study to evaluate how poor communication and planning can have serious long-lasting impacts on stakeholders. This Station Spotlight will explore how this gap in planning occurred, how it has affected passengers, and how future efforts can learn from the mistakes made at the Vendôme station.

Station layout

Metro Vendôme’s main building on the north side of the Exo train tracks has two access points. These entrances (on Boulevard Maisonneuve and Avenue de Marlowe) are displayed on our station poster. Both have 11 stair-steps connecting the ground level to the terminal level, and one side also has elevator access. There are two additional elevators at the terminal level, one for each of the platforms, which are separated from the terminal by 23 stair-steps. There is one more entrance on the exterior parking of the Glen Site that is connected to the metro and train stations by a tunnel with stairs. For six years after the construction of the superhospital, this was the only direct way to get between the two areas.

Before 2021, there were no elevators at all at this station. It was only after the construction was completed that this crucial element was added to a station where accessibility is so important. The renovations also added another access point for the station located directly on the Glen Site, which also has elevators down to a tunnel to reach the stations. The implementation of elevators and an accessible tunnel under the Glen Site is a relatively new addition, with the changes having only been completed in Spring 2021. Yet, the MUHC’s move to the Glen Site was completed in 2015, meaning that access between the metro station and the hospital was an obstacle to vulnerable passengers for over six years. Could this have gone differently?

Long-term repercussions

Up until the completion of the 2021 renovations, moving between the hospital and the metro station was a challenge riddled with inaccessibility. The lack of elevators in the station made it impossible for wheelchair users and parents with strollers, among others, to enter or leave the station with ease.

Furthermore, the separation of the station from the hospital by the railroad tracks meant having to walk along Boulevard Maisonneuve to Boulevard Decarie to then reach the hospital.

This is a dangerous intersection, one that benefits cars while being hostile to pedestrians and cyclists; it needs to be redesigned in its own right, and it definitely did not need more pedestrian traffic until it does get adapted to be more multimodal. Additionally, the narrow sidewalk declines and inclines as it goes below the tracks. This can become even more difficult for disabled users in winter months.

In planning for accessibility, some obstacles are major, while others are simply inconveniences. However, public spaces and the spaces which help us access them should be equally welcoming of all users, and be especially considerate of how the spatial design affects those who are disabled, for whom an accessibility inconvenience is usually followed by many others. It may seem like a low-effort task to move around obstacles, but asking this of hospital goers may actually represent a physically and emotionally stressful obstacle. This is especially true for those who are disabled, friends and family visiting their loved ones, or even hospital workers at the end of a long and hard shift. If they choose to mix their modes between biking and transit to and from work, is the infrastructure present for them to do this? If visitors or employees have children in daycare, are they able to access the area with their strollers with minimum inconvenience?

Why did these obstacles exist in the first place? The MUHC move was first announced in 2006, and took an enormous amount of planning before it was completed 9 years later. In 2007, the Montreal metro’s first elevator-equipped stations were also opened, with the STM announcing plans to retrofit elevators into their existing stations. Although proximity to healthcare institutions was cited as one of their prioritization criteria, plans did not appear to retrofit elevators at Vendôme until October 2017, over two years after the new Glen Site had become operational. Given the project was only completed in 2021, this left disabled and reduced mobility patients as well as hospital employees who commute to the hospital daily (among others) struggling to access the hospital from this station for over six years.

Planning a better connection

The Glen Site’s proximity to the intermodal hub at Vendôme was undoubtedly an important factor in the decision to move the MUHC there. However, this vision necessarily relied on accessibility between hospital and station in order to be fully realized. Unfortunately, this accessibility was neither planned for in the MUHC’s move nor accounted for by the municipality in a timely manner. This gap in planning is symptomatic of the lack of communication between developers and the municipality as well as the systematic failure to prioritize accessibility in transportation planning.

It is understandably difficult to achieve this level of coordination between various groups and stakeholders, but it is so crucial for a project of this size and nature to account for the accessibility needs of all its users.

The complexity of the issue of accessibility at this location is compounded by the multiple stakeholders who have a stake in the area. The MUHC, the STM, and Canadian Pacific Railway (who own the tracks) all had to communicate and work together in order to make this project happen. It is understandably difficult to achieve this level of coordination, but it is so crucial for a public service project of this size and nature to account for the accessibility needs of those who will use it. Yet, the lack of connectivity between Vendôme and the MUHC exhibits once again that point-to-point transit accessibility is often an afterthought.

Infrastructure projects are expensive, and integrating accessibility elements often represents additional costs, which may tempt stakeholders to push their implementation to a later date. This would not be the case if universal accessibility were mandated by law and federal protocols were established to help support both public and private development projects in their implementation.

DESIGN SPOTLIGHT

The project at Vendôme aimed to implement universal accessibility at the stations and integrate a smooth and accessible passageway between the station and the hospital. Even after the retrofit was completed, there remain some accessibility obstacles that require extra attention. One of these is the lack of hand railing in the new tunnel.

The images above demonstrate on a micro scale the challenges of planning a project with numerous different stakeholders and how this can impact users with reduced mobility.

On the hospital side of the tunnel, a handrail was installed from edge to edge, an important consideration for elderly and disabled users of the tunnel who may need to hold on or rest. As can be seen on the image above, the STM side of the tunnel only has a few handrails spread out throughout the area, similar to what can be found in many of Montreal’s metro stations.

For a tunnel of this length, a handrail can make a big difference in comfort and safety for certain stakeholders. Even the visual contrast between the two images is stark: accessibility creates a much more welcoming space for everyone.

In the United States, the Americans with Disabilities Act represents that legal framework, and programs such as the ADA National Network have emerged to help guide and fund projects to ensure they implement the right infrastructure at the planning stage. Accessibility at Vendôme and the Glen Site would surely have been improved if Canada had legally enforced accessibility requirements at the federal level. We need policy makers and lawmakers to push for this kind of legal framework to be put in place so that future projects do not repeat the same coordination errors that occurred at Vendôme.

Retrofitting accessibility in response to existing obstacles is a crucial part of making our cities universally accessible, but hopefully this case study serves as a lesson for future projects so that, moving forward, accessibility can be implemented proactively.

In the end, the Vendôme accessibility project was a crucial and successful implementation. The new entrance at the MUHC, along with the pedestrian tunnels which connect the hospital to the metro and Exo stations are well-integrated and have improved the area’s accessibility and connectivity. There is no doubt, however, that this implementation was far too late, and still imperfect. A project of this scale should account for these needs in advance and the necessary accommodations need to be implemented in a timely manner, and this cannot be said about the MUHC-Vendôme connection. Retrofitting accessibility in response to existing obstacles is a crucial part of making our cities universally accessible, and it is a relief that this project has finally been completed, but hopefully this case study serves as a lesson for future projects so that, moving forward, accessibility can be implemented proactively.